DAOs and the Complexities of Web3 Governance

5

1

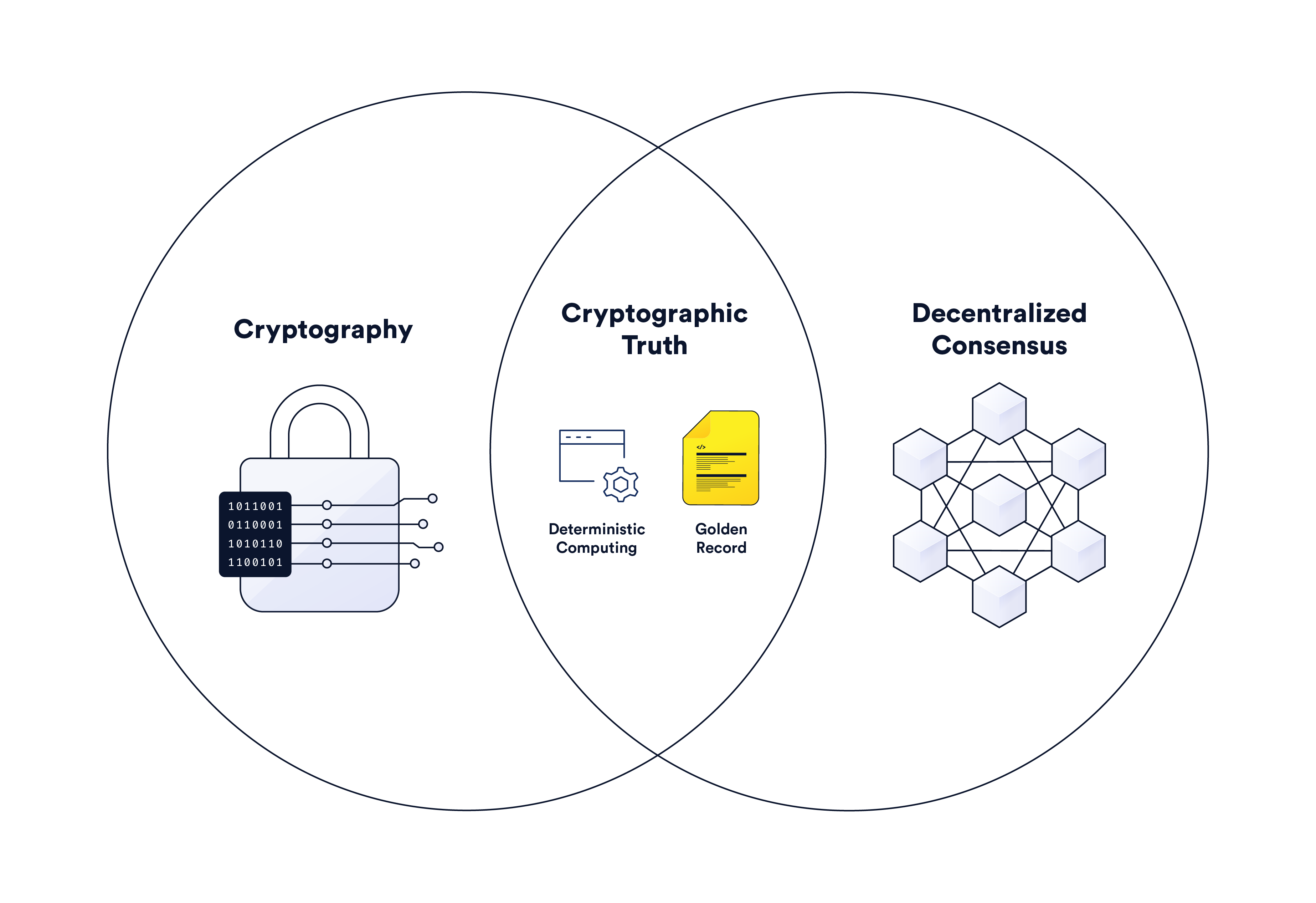

Web3 was born out of the failure of centralized institutions to manage society’s financial and social infrastructure in a secure, equitable, and transparent manner. Web3 is founded upon trust-minimized distributed networks, such as blockchains and oracles, which utilize cryptography, consensus protocols, and mechanism design to manage digital infrastructure—a transition away from trust in human third parties in favor of technologically enforced guarantees, a concept known as cryptographic truth.

Beyond DeFi and NFTs, trust-minimized digital infrastructure has enabled a new type of blockchain-based social structure called a DAO. DAOs empower independent entities to collectively govern open-source infrastructure and/or democratically manage shared assets, particularly by codifying specific processes into smart contracts that are enforced by blockchains. In essence, DAOs aim to expand the notion of trust-minimization to collective decision-making by humans.

The following blog post presents a nuanced perspective on DAOs, starting with an educational primer on the basics of DAOs before discussing the benefits and tradeoffs every DAO must optimize around if they are to achieve sustainable success.

The Basics of DAOs

To understand the benefits and tradeoffs of DAOs, it’s important first to define what a DAO is, look at various types of DAOs, outline their responsibilities, and lay out the different DAO tooling and governance structures that exist today.

What Is a DAO?

DAO stands for “decentralized autonomous organization.” The general purpose of a DAO is to collectively make decisions about something in a more distributed, transparent, and trust-minimized manner than is possible in traditional organizations. In a simple sense, a DAO is a new type of human organizational structure that allows people to work towards a common goal based on a common understanding that all participants are able to independently verify how the organization functions.

One of the unique aspects of DAOs is their use of blockchain-based smart contracts, which codify some or all of the processes by which they execute decisions and assign ownership. The incorporation of smart contracts is foundational to their innovation because it allows the rules governing how the DAO functions to be made fully transparent to members and highly resistant to tampering by members or external entities. This is because code running on blockchains (i.e. smart contracts) is publicly auditable and secured by a decentralized network of nodes.

It should be noted that while the word “autonomous” is part of the term DAO, DAOs are not fully autonomous. DAOs are made up of humans and therefore require manual actions from users to function, such as needing users to conduct votes, deploy code, and debate proposals. The use of autonomous in the term DAO stems from the idea of hardcoding specific functions of the DAO as immutable smart contracts. However, humans still need to interact (provide inputs) with the smart contracts (code) for them to execute actions (outputs).

Types of DAOs

While still in their infancy, DAOs can be categorized into six general types:

Protocol DAOs support the development and management of decentralized applications (dApps) or the infrastructure used by dApps. Protocol DAOs are largely concerned with stewarding open-source technology, similar to a company or foundation.

- Tezos is a blockchain using a DAO-like on-chain governance structure to activate protocol upgrades, most notably through a delegate-based voting system that requires supermajority consensus for approvals.

- MakerDAO is an organization that manages the decentralized stablecoin DAI. DAO participants are responsible for setting protocol parameters, such as adjusting interest rates, adding/removing collateral types, and onboarding/offboarding core unit teams.

Investment DAOs make and manage investments using funds located in a treasury under the DAO’s control. Investment DAOs are predominately focused on generating profits for their members, similar to private equity funds or hedge funds.

- BitDAO is a DAO that grows its treasury through a variety of strategies voted on by BIT token holders. BitDAO claims to have allocated over $638M USD to Web3 projects.

- MetaCartel Ventures (Venture DAO) is a for-profit DAO that makes investments into early-stage dApps. It’s focused on embodying a community-oriented membership structure and offering more flexible participation than traditional venture capital funds.

Cause-based DAOs manage funds and initiatives meant to support specific causes. Cause-based DAOs are centered around achieving collective goals in areas such as philanthropy, politics, and public goods, similar to traditional organizations like charities, lobbying groups, and grant programs.

- Gitcoin is a DAO that manages a platform where users can collectively fund public goods for Ethereum and other open-source blockchain-based projects via a quadratic voting model.

- Big Green is a DAO that awards philanthropic grants geared toward helping schools, communities, and families learn how to grow their own food.

Social DAOs manage a shared social space, collectively own something of artistic value, and/or cultivate culture and events for their members. Social DAOs bring social communities together around entertainment, art, games, and other social aspects of life, similar to modern social clubs.

- Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC) is a limited NFT collection where the NFT doubles as membership in the DAO, giving holders special perks.

- Krause House is a social DAO made up of basketball lovers that aim to own an NBA team someday. The Krause House DAO already owns Ball Hogs, a team in The Big3 basketball league.

Data DAOs develop and manage data under the control of the DAO. Data DAOs are designed around pooling users’ data or developing unique data products in order to sell it to third parties who want to use it, such as to create AI algorithms or market research.

- dClimate is a marketplace for climate data, forecasts, and models that empower both users wanting to sell novel datasets and institutions wanting to buy them. The DAO evaluates the data from publishers to help maintain high-quality and proper network incentives.

- Delphia is a planned robo-advisor that will pay people for their personal data in a native token. Delphia will pool users’ personal data together and use it to design investment strategies while the native token will give users access to the strategies.

Network states, a term coined by Balaji Srinivasan, are DAO-like structures used to create new legally recognized societies. As Balaji defines it in his book The Network State: How To Start a New Country,

“A network state is a social network with a moral innovation, a sense of national consciousness, a recognized founder, a capacity for collective action, an in-person level of civility, an integrated cryptocurrency, a consensual government limited by a social smart contract, an archipelago of crowdfunded physical territories, a virtual capital, and an on-chain census that proves a large enough population, income, and real-estate footprint to attain a measure of diplomatic recognition.”

The Responsibilities of DAOs

DAOs can ultimately be designed to perform any type of task, but some of their most common responsibilities include:

- Approving upgrades to an open-source protocol, such as voting on whether the proxy contracts of a protocol can be upgraded to support a new implementation with different logic (i.e. code) or to approve the release of a new standalone version of the protocol that users can migrate to once deployed.

- Adjusting parameters within a dApp, such as changing the interest rate for a decentralized stablecoin or deciding whether to support a new collateral type in a lending market.

- Submitting improvement proposals and debating their merits, such as creating a formal proposal to change something about the protocol/DAO or challenging the premises of other proposals prior to votes.

- Directing protocol-owned funds to investments or external accounts, such as awarding grants from the DAO’s treasury to recipients or deciding whether the DAO should invest in a limited-edition NFT.

- Managing leadership, such as voting people into or out of management positions, overriding leadership decisions, or changing the underlying organizational structure of the DAO.

- Arbitrating disputes derived from the usage of the protocol, dApp, or DAO-managed infrastructure, such as determining if users should be compensated for an unexpected hack or bug in the protocol.

- Determining the long-term roadmap and vision of the protocol, such as discussing whether the DAO should expand upon an existing use case vertical or deciding what blockchains/layer-2 networks it should support.

- Calibrating the value capture mechanism of the protocol, such as how much in user fees to extract, whether or not to burn tokens, or if DAO members should receive a dividend.

DAO Tooling

DAOs make use of a standardized set of tools to fully function, oftentimes combining multiple tools listed below to form a multi-layered DAO structure.

- Governance token: A cryptocurrency token issued by the DAO which grants holders specific powers within the DAO. Most notably, governance tokens are often required by DAO members in order to cast votes (e.g. 1 token = 1 vote).

- Multi-signature wallet: A smart contract that requires m-of-n predefined addresses to sign a message that directly implements changes to the protocol. Multi-sigs are often used by DAOs to implement on-chain changes to a protocol based on an off-chain snapshot by smaller predefined committees or during emergency situations as a security measure such as mitigating governance attacks.

- Voting contract: A smart contract that coordinates an on-chain token-weighted vote on a proposal that must meet a predefined threshold (e.g. 66% yes) and quorum (e.g. 2% token holder participation) by DAO members or DAO delegates in order to be approved. Results can be implemented by a multi-sig or via proposals that are submitted as executable code, as seen in Compound’s governance alpha voting contract.

- Delegation system: A mechanism that allows governance token holders to delegate their voting power to other parties, such as representatives, that vote on their behalf.

- Off-chain snapshot: An off-chain platform to conduct token-weighted votes via signed off-chain messages, where a snapshot of on-chain balances and addresses is taken to determine voting power. The results are used to influence subsequent actions as defined by the DAO. This approach is advantageous because members don’t have to pay on-chain transaction fees to vote, thereby increasing the chances of more robust community participation.

- Discussion forum: Nearly all DAOs have a social layer that allows members to come together and present and debate ideas in an open manner. The most popular mediums involve either dedicated governance forum websites like Discourse or a Discord server or Telegram group.

- Reputation systems: While still in the early stages, on-chain reputation is being explored as a way to give more weight to individuals who routinely participate in, provide valuable insight to, or support the DAO. One proposed method is soulbound tokens, which assign non-financial merits to user addresses as tokens, giving them some form of on-chain reputation, or “soul”.

DAOs will have to decide how they want to combine these tools and others to create a holistic governance process that meets their members’ own desired balance between efficiency, cost, and trust-minimization. Each DAO will have a different notion of optimization based on the philosophy and values of its members and the explicit purpose of the DAO.

DAO Governance Structures

Forming consensus is one of the most important yet challenging aspects of any DAO, as it’s how decisions are made in a decentralized manner. Below are a few governance structures currently used to form consensus, involving a combination of some of the tools outlined above.

Direct on-chain democracy is when members vote on a proposal directly on-chain, with a threshold that must be met for the motion to be approved. Most DAOs employing direct on-chain democracy use token-weighted voting, where the more tokens a user holds, the more weight they have in votes (generally 1 token = 1 vote). This is the most common and simplest approach to achieving consensus within a DAO given its minimal complexity and overhead and Sybil-resistance properties.

Direct off-chain democracy is when a DAO conducts votes off-chain using snapshots, and some threshold must be met for approval. Most direct off-chain democracies also utilize token-weighted voting but require a multi-sig of trusted entities to faithfully push the proposed change on-chain. Thus, off-chain democracies require an element of trust that the multi-sig signers will vote in alignment with the snapshot results of the DAO.

Representative democracy is when a DAO makes use of representatives who vote on-chain to approve proposals submitted to the DAO. Representatives are generally elected by the DAO and may make use of off-chain snapshots to gauge the interest of the wider DAO community prior to some or all votes. The DAO may also incorporate methods of overriding or changing its representatives should there be a significant lack of support or dissent from their decision.

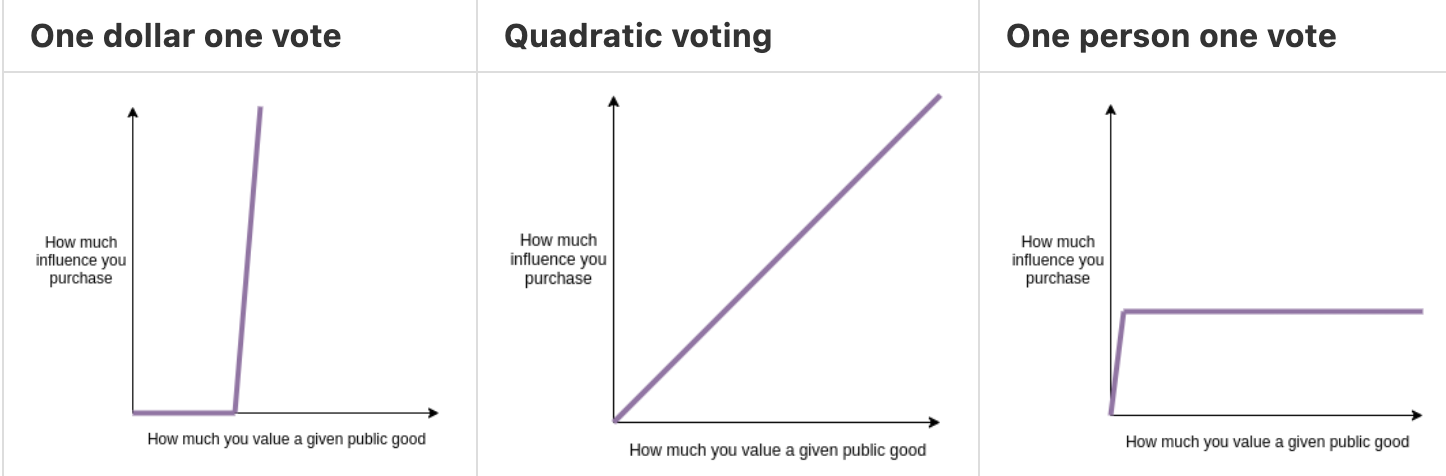

Quadratic democracy is a governance structure based on quadratic voting, represented by the equation: cost to the voter = (number of votes)2. For instance, one vote for a proposal may require a member to have one governance token, but five votes may require twenty-five governance tokens. Quadratic voting is a method of preventing the outcome of DAO votes from being determined by a few members with the highest token balances, resulting in a dynamic where a large number of individuals can become equally or more impactful when they vote in unison. However, a Sybil-resistance mechanism is required to make quadratic voting practical in order to prevent the spoofing and splitting of tokens across wallets.

D3LAB is a project working on a new Sybil-resistant quadratic voting system specifically for DAOs called Probabilistic Quadrating Voting (PQV). D3LAB received a Chainlink grant to further develop the system.

Though not in the scope of this article, there also exist many decentralized crypto communities that are bound together by the ownership of tokens but are not technically DAOs. These communities are often supported by more traditional organizational structures such as development companies and open-source foundations that contribute to and maintain protocols. However, they also benefit from anchoring themselves to blockchains for stronger incentive alignment and transparency.

The Benefits of DAOs

It’s hard to truly know the long-term benefits of DAOs until they are tested at scale over a longer period of time, but some of their potential benefits include:

Transparency

The rules of a DAO (open-source code) and the activity of its participants (on-chain actions, forum posts) are generally transparent for all to view and audit, enabling people to fully understand how decisions are and were made over time and how power is distributed amongst members. This contrasts with traditional organizations that are generally more opaque and require that users trust the organization to document its decision-making processes fully, accurately, and immutably.

Democratization

DAOs often empower any member to submit proposals, challenge their merits, and vote on whether they are accepted or denied, resulting in a more democratized process where members can come together to influence the direction of the DAO. This differs from traditional organizations that favor more hierarchical structures where the CEO, owner, or a board of directors have exclusive rights to execute most decisions while other stakeholders have a very limited ability to make their voice heard.

Trust-minimization

The structure of the DAO, how it forms consensus, and how consensus is turned into action are often hardcoded into open-source smart contracts deployed on public blockchains, making it difficult for any single entity or small group to tamper with governance processes once they are agreed upon. This differs from traditional organizations where management processes are often facilitated and carried out by a centralized entity, with the rules outlining these processes expressed as vague, complex, and sometimes private legal contracts that can be costly to dispute, slow to enforce, or difficult to obtain deterministic outcomes from.

Global

DAOs often allow anyone in the world with an Internet connection to participate without revealing every aspect of their identity, leading to social structures that can inherently remove potential biases around gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status, sexual orientation, nationality, and other personal identifiers. This contrasts with traditional organizations where members are generally publicly known figures, making it hard to have more pure forms of meritocracy.

The Tradeoffs of DAOs

Instead of discussing the downsides of DAOs, it’s more illuminating to look at the tradeoffs they face through the lens of different dichotomies they have to navigate. These dichotomies don’t have a right or wrong implementation strategy but come with pros and cons that must be individually weighed and decided upon to fit the priorities of each DAO. Interestingly, nearly all traditional governance structures are subject to similar tradeoffs, so DAOs are not unique in facing these challenges.

Early-Stage vs. Late-Stage Members

Power in a DAO can start out in or come into the hands of a few large token holders, particularly when token-weighted voting is implemented. This often happens because a DAO’s founders and/or early investors are awarded a higher percentage of the governance token supply.

While this introduces centralization concerns, the more difficult question is if early founders and investors are justified in having the greatest voting power and influence given that they created the DAO and committed the most time and resources to its incubation. If so, what is a reasonable percentage? The challenge is that community members who join at a later stage may feel their voices are being drowned out by a few select members, putting into question the value of their participation.

Ultimately, this dichotomy centers around how to reward and empower early-stage participants who took on greater risk and provided more resources without limiting the ability of those that come later to rise through the ranks and make their voices heard. This is no different than traditional social formations, which don’t want to penalize investment and success but do need to maintain a certain level of upward mobility.

Decentralization vs. Efficiency

For a DAO to maintain trust-minimization, there must be checks and balances on power in order to mitigate quick, emotional, or rash decisions that are not supported by the wider community, as well as to protect the DAO against governance attacks and undesirable infiltration by outsiders. Checks and balances are a key design decision in modern democracies, serving as a mechanism to prevent the build up of too much centralized power, particularly by decentralizing power and clearly defining the scope and responsibility of each segment.

The challenge is that decentralization often creates inefficiencies that inhibit DAOs from executing in a timely manner, such as limiting their ability to capitalize on real-time opportunities or quickly patch unexpected vulnerabilities. The inability to be agile, along with the time and resource sink accompanying multi-layered decision-making processes, can make it harder for DAOs to compete with more centralized hierarchical competitors, especially in new, fast-changing, and open-source technology markets.

The dichotomy here revolves around how to maintain the core value of trust-minimization that makes DAOs valuable while also empowering the DAO to operate efficiently without long, drawn-out processes for every decision. It leads to a broader question around whether protocols can transition from a traditional centralized governance structure to a more decentralized DAO structure over time. If so, what is a realistic timeframe and which components should be prioritized first? Traditional governments have similar challenges in how to uphold fundamental human rights and engrained laws while also being flexible enough to consistently maintain high levels of success and quickly ward off new threats.

Stabilization vs. Growth

When it comes to decentralized, trust-minimized technologies, some express the view that “no governance is the best governance.” The reason for this is that humans generally have a poor historical track record of maintaining fair, safe, and stable governance systems, making any form of governance an attack vector for internal and external corruption. While there is an element of truth to such statements, the reality is that nearly all social structures are dynamic in nature, meaning they are constantly evolving to serve the developing needs of their members.

The difficulty with DAOs is striking the right balance between two contradictory perspectives: prioritizing the ossification of the protocol’s rules and slowly removing the DAO functionality over time versus continuing to grow the protocol and maintain flexibility, which generally necessitates expanded use of the DAO. This is an emerging challenge today, with DAOs having ongoing internal political debates rooted in disagreements about what the DAO’s vision should be—mostly between those who want to adhere to a strict interpretation of the protocol’s original vision and those who want to expand beyond the protocol’s original use case in order to capture a larger market.

The dichotomy boils down to having a clear manifesto and foundational vision that the DAO can align behind while also incorporating structures that allow it to be updated should the values of its members evolve over time. This dynamic appears throughout history, as demographic and contextual changes sometimes result in contentious differences of opinion about what the collective vision of a society is or should be in the future.

Leaderless vs. Leadership

Perhaps due to their ideology of decentralization, many argue that DAOs should be leaderless. While a leaderless society may work in some niche situations, historically social structures lacking quality leadership have not operated as effectively as those with clear and respected leaders. Leaderless societies are subject to well-known phenomena such as the tragedy of the commons, where the common good is neglected because no one assumes responsibility for managing it; power vacuums, where the absence of power leads to internal conflicts in the rush to fill the void; or simply stagnation due to a lack of long-term thinking and discipline required to fully actualize a complex vision.

The downside of leaders is that they can become malevolent when given too much power, which negates that very benefit of a decentralized autonomous organization. This is why some DAOs have already begun to experiment with representative structures, such as Synthetix’s utilization of “The Spartan Council”—a seven-member group elected by the DAO to make decisions on improvement proposals submitted by users. Synthetix supplements The Spartan Council by taking snapshot votes off-chain to gauge the Synthetix token holder community’s sentiment prior to making votes.

The dichotomy here is how to provide enough motivation and autonomy to attract, empower, and protect ethical leaders with real vision while also keeping their power in check should they deviate from the DAO consensus. It’s an interesting and polarizing phenomenon because the quality of leadership in traditional governments has led to some of the best- and worst-run societies in history.

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Priorities

Another prominent DAO dynamic is how to balance the priorities of members. For instance, some DAO members are focused mostly on short-term growth, involving how to capture more value or attract mercenary capital, even if it sacrifices the long-term flexibility of treasury resources. However, other DAO members may be focused on how to achieve real adoption and long-term sustainability, which doesn’t always directly benefit DAO participants in the short-to-medium term.

This dynamic is intertwined with the leaderless vs. leadership and the early-stage vs. late-stage member dichotomies. Most notably, leaders are often members who have been around a while or perhaps founded the project. Thus, they generally favor taking a longer-term perspective given that they may have been well compensated up-front and have more at stake—financially and reputationally—in the protocol’s success. Alternatively, newer members who generally have less at stake will prioritize immediate satisfaction or simply leave if their wishes are not implemented by a certain timeline.

The dichotomy often appears to come down to maintaining a long-term plan necessary for success by not oversteering to accommodate for every complaint while at the same time not ignoring any appropriate concerns of DAO members. Traditional governance systems deal with this when introducing major policy changes. On one end they need to account for a certain level of discontent from citizens when they change course, but a failure to achieve enough support and deliver tangible results along the way will ensure the policy change never has the runway required for it to be put fully into motion and bear fruit.

Knowledgeable vs. Unknowledgeable

Blockchain-based technologies are fundamental to the value proposition of DAOs. However, only a small number of people have the knowledge to fully understand the smart contracts underpinning DAO functions, as well as the technical intricacies of the blockchain(s) they run on. Furthermore, there are a variety of legal and business considerations that need to be taken into account in order to make educated decisions on certain DAO proposals such as new business ventures. This introduces reliance on sophisticated members—particularly developers, lawyers, subject-matter experts, and founders—to break down certain aspects of proposals prior to the DAO conducting a vote.

The challenge is that most DAO members will not be able to properly weigh the risks and benefits without help from sophisticated members. For instance, sophisticated members are needed to abstract away technical jargon or provide detailed insights into specific legal and economic questions. Given the importance of sophisticated members, the question then becomes whether they should have more weight in decision-making or at least be rewarded by the DAO.

This creates a dichotomy where DAOs need to incentivize sophisticated members to remain active and reliable without creating an over-reliance or over-empowerment that drowns out other members who then choose not to participate. Traditional governments deal with similar concerns in how to properly put faith in experts in situations that require them without drowning out the dissenting opinions of citizens and other experts.

Nothing-at-Stake vs. Hyper-Financialization

All DAOs must determine the right barrier to participation. If there is no barrier to participation, then the system can become vulnerable to Sybil attacks and anyone can influence decisions, even if they have no historical activity or financial stake in the DAO. However, most DAOs have some criteria necessary for participation, such as holding the native governance token.

The problem however is that someone could acquire a large percentage of governance tokens or even borrow tokens temporarily to gain influence in a governance vote, opening up DAOs to so-called governance attacks. This introduces a dynamic where DAOs want some barrier to participation in order to prevent Sybil attacks, but don’t want to base their entire organizational structure around financial capital. Without methods of incorporating participation via non-financial merits, DAOs can be subject to hyper-financialization—all decisions come down to financial power. Fortunately, this is an area being explored by top minds such as Ethereum Co-Founder Vitalik Buterin who, in a paper titled Decentralized Society: Finding Web’s Soul, presents the idea of creating soulbound tokens to award on-chain users with non-financial merits.

This creates a dichotomy around how to ensure that members have some form of stake and/or reputation in the DAO without hyper-financializing the DAO. Society today is plagued with similar questions around how much of a role financial capital should play in collective decision-making.

The Future of DAOs

Ultimately, DAOs are simply a new tool that can be used to design social structures in a more trust-minimized way. However, DAOs are not a magical solution that fixes all the governance problems that have plagued society for thousands of years.

The truth is that there is no perfect governance system. However, Web3 offers builders the ability to experiment more flexibly with governance systems and users the opportunity to get closer to protocols that support governance systems in alignment with their own personal values and beliefs. Some may prefer no governance while others may opt for more hands-on governance needed to support more complex systems—and that’s totally fine. People’s views will also evolve over time too as some DAO structures fail and simply are not adopted while other DAOs are successful and thrive.

It’s an exciting design space, but one that is still very much in its infancy. It’s unclear how DAOs will evolve into the future, so Web3 builders don’t need to be in a rush to launch one. Hopefully, with enough experimentation, a diverse marketplace of DAO designs emerge which support a broad range of values. At the same time, the marketplace as a whole embodies an overall increase in governance transparency and trust-minimization while still being dynamic enough to compete with Web2 systems.

To learn more about Chainlink, visit the Chainlink website and follow the official Chainlink Twitter to keep up with the latest Chainlink news and announcements.

The post DAOs and the Complexities of Web3 Governance appeared first on Chainlink Blog.

5

1

Manage all your crypto, NFT and DeFi from one place

Manage all your crypto, NFT and DeFi from one placeSecurely connect the portfolio you’re using to start.