Why Railgun Project co-founder talked to the feds — and what’s next for crypto privacy

0

0

The way Alan Scott tells it, he thought he was being scammed.

As a co-founder of the Railgun Project, a group that educates on and contributes code to the Railgun privacy protocol, he is accustomed to federal agents’ scepticism.

So, when an invitation to speak at the Virtual Currency Symposium — which Scott describes as the biggest international conference for law enforcement agencies looking to catch crypto bad guys — darkened his inbox, he thought it was a con.

“It’s not every day you get somebody from the FBI write to you and say, ‘Hi, we would like you to talk at our conference,’” Scott told DL News in an exclusive interview.

The invite turned out to be genuine.

In late August, Scott stepped up on a Milwakue stage after the deputy director of the FBI’s keynote to tell people policing privacy protocols like his that — contrary to popular belief — these tools are not just for criminals.

That’s a hard sell.

Authorities have spent the past few years cracking down on privacy protocols and crypto mixers.

In April, the Department of Justice arrested two co-founders of Samourai Wallet, a Bitcoin wallet with a built-in crypto mixer.

A Dutch court convicted Tornado Cash developer Alexey Pertsev of laundering $2.2 billion in illicit assets in May, and the European Union is looking to ban crypto mixers and privacy tokens.

But Scott is on a campaign to convince law enforcement agencies, politicians, and the public at large that privacy tools can bolster honest users’ security.

Vitalik’s favourite privacy tool

Railgun has largely flown under the radar since its 2021 debut.

But in recent months, Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin used Railgun on several occasions and promoted the protocol on X to his 5.3 million followers.

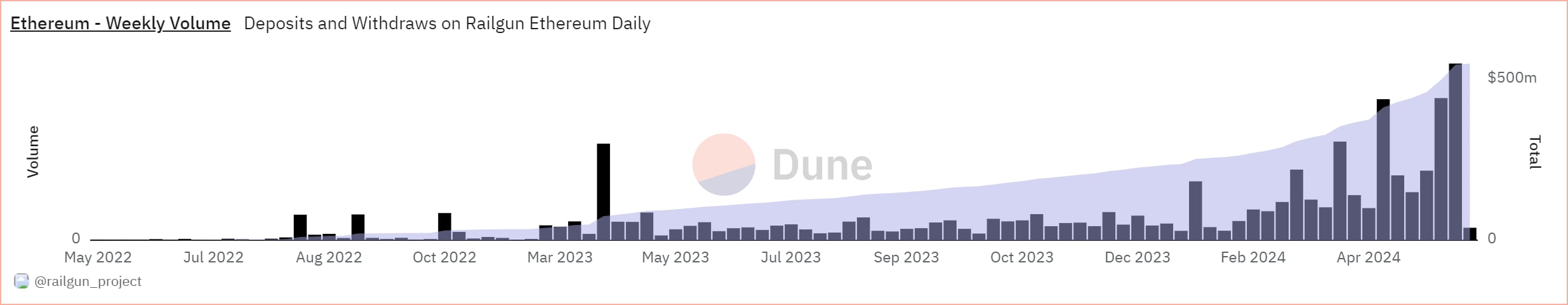

The high-profile attention had an effect. On May 27, the protocol recorded its highest-ever weekly volume of $47 million.

Railgun distinguishes itself from similar projects, such as Tornado Cash, with its Proof of Innocence feature, which is designed to prevent bad actors from using it.

This lets users create a cryptographic proof that shows the money they put into the protocol didn’t come from wallets associated with stolen funds or illicit activity, while at the same time keeping the origin of the money secret.

The thinking is that if honest Railgun users generate these proofs, bad actors attempting to launder crypto through the protocol will be the only ones left without them — empowering crypto exchanges and law enforcement to identify them.

Currently, Proof of Innocence only flags crypto addresses that the Office of Foreign Assets Control has put on its sanctions list, but Scott said Railgun contributors want to change that.

Contributors are working on a secure way to allow law enforcement and crypto security experts to update the list of bad actors in real-time — even if the addresses are not yet on the official OFAC list.

“What if law enforcement around the world would be able to contribute to this?” Scott said.

Scott’s main Railgun contribution is to research as well as facilitate communication and collaboration with other projects.

In recent months, he’s been advocating on behalf of the Railgun protocol and other privacy protocols — telling everyone from casual memecoin traders to the FBI why so many people treasure privacy.

“Overwhelmingly, the response is quite positive,” Scott said.

Privacy protocols under siege

While Scott’s been busy talking with federal agents, anonymity advocates are absolutely alarmed at how privacy is being threatened.

They point at Pertsev’s conviction as well as the US Department of Justice charging two more Tornado Cash developers for running a scheme that enabled criminals to launder over $1 billion of illicit funds.

Privacy advocates argue that these developers are unfairly penalised by others using the tools they created to commit crimes.

“It definitely creates a negative bias in privacy,” Scott said. “There’s even a bit of a chilling effect around privacy because people are like, ‘I don’t want to go to jail for writing code.’”

Such chilling effects include developers choosing not to write and publish code relating to privacy, stifling innovation.

Another example of the chilling effect is that traffic to Wikipedia articles containing keywords tracked by the Department of Homeland Security dropped following revelations about NSA surveillance in 2013.

However, Scott said, he’s not all that worried about Railgun facing a similar fate as Tornado Cash.

“I do find it unfortunate that those dudes are in jail,” he said, adding that “there’s a lot of people developing privacy who aren’t in trouble.”

He pointed to long-running crypto privacy projects like Aztec and Zcash, among others that aren’t facing the same issues as Tornado Cash.

Privacy nuances

There are also signs authorities are starting to recognise the nuances around crypto privacy.

“We believe that there is a difference between obfuscation and anonymity enhancing services that support privacy,” Brian Nelson, the Treasury’s Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence, said at the recent Consensus crypto conference.

Nelson said he understood the desire for privacy in the context of public blockchains, and that the Treasury wants to work with the crypto industry to identify and collaborate on tools that can enhance privacy.

Nelson’s comments, while positive, mean Scott and other privacy advocates like him will likely have a busy time ahead of them.

Tim Craig is a DeFi Correspondent at DL News. Got a tip? Email him at tim@dlnews.com.

0

0